Can machines think? Can artificial intelligence be as smart as humans?

A new study suggests that artificial intelligence may be able to do it.

In a non-verbal Turing test, a research team led by Professor Agnieszka Wykowska of the Italian Institute of Technology found that Behavioral variability can blur the distinction between humans and machines, which can help robots look more like Humanity.

Specifically, their AI program passed the nonverbal Turing test by simulating the behavioral variability in human reaction times when playing games with human teammates about matching shapes and colors.

A related research paper, titled “Human-like behavioral variability blurs the distinction between a human and a machine in a nonverbal Turing test”, has been published in the scientific journal Science Robotics.

The research team said the work could provide guidance for future robot designs that endow robots with human-like behaviors that humans can perceive.

For this study, Tom Ziemke, a professor of cognitive systems at Linköping University, and Sam Thellman, a postdoctoral researcher, believe that the findings “blur the distinction between humans and machines” and make very important contributions to people’s scientific understanding of human social cognition. valuable contribution.

However, “human likeness is not necessarily an ideal goal for AI and robotics development, and making AI less human-like may be a wiser approach.”

Pass the Turing Test

In 1950, Alan Turing, the “father of computer science and artificial intelligence”, proposed a test method for determining whether a machine has intelligence, the Turing test.

The key idea of the Turing test is that complex questions about machine thinking and the possibilities of intelligence can be tested by testing whether humans can tell whether they are interacting with another human or a machine.

Today, the Turing test is used by scientists to assess what behavioral characteristics should be implemented on an artificial agent to make it impossible for humans to distinguish computer programs from human behavior.

Artificial intelligence pioneer Herbert Simon once said: “If programs exhibit behavior similar to that of humans, then we call them intelligent.” Similarly, Elaine Rich defines artificial intelligence as “the study of how to Let computers do things that people do better today.”

The non-linguistic Turing test is a form of the Turing test. Passing the non-verbal Turing test is not easy for AIs because they are not as skilled as humans at detecting and distinguishing subtle behavioral characteristics of other people (objects).

So, can a humanoid robot pass the nonverbal Turing test and embody human characteristics in its physical behavior? In the non-verbal Turing test, the research team tried to figure out whether an artificial intelligence could be programmed to change its reaction time within a range similar to the variation in human behavior to be considered human.

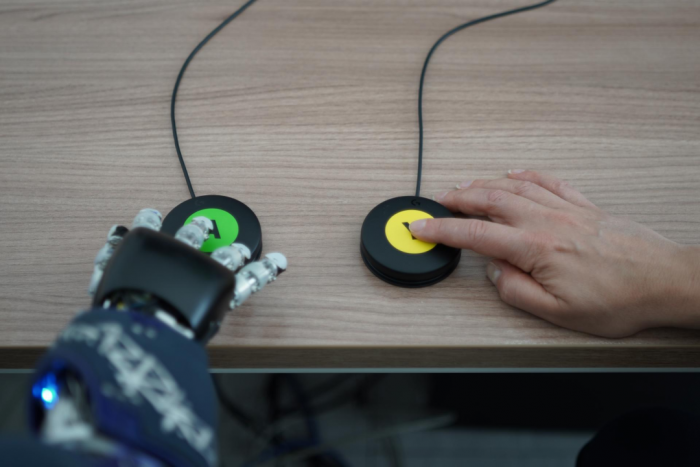

To do this, they arranged humans and robots in a room with screens of different colors and shapes.

Image map | Robots and humans perform tasks together. (Source: The paper)

When the shape or color changed, the participants pressed the button, and the robot responded to this signal by tapping the opposite color or shape displayed on the screen.

Image figure | Responding by pressing a button (source: the paper)

During testing, the robots were sometimes controlled remotely by humans, and sometimes by artificial intelligence trained to mimic behavioral variability.

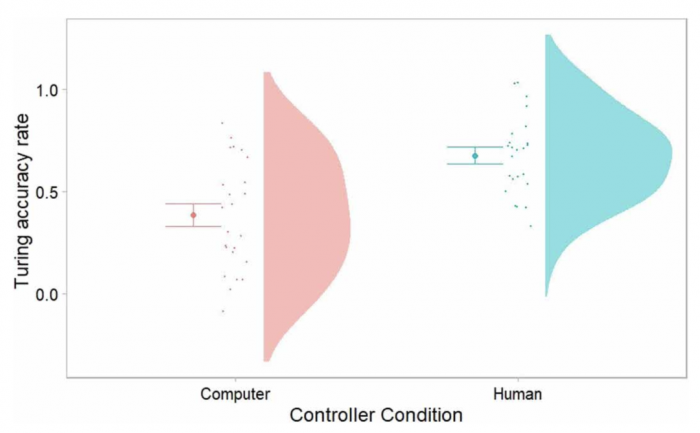

Figure | Participants were asked to judge whether the robot behavior was pre-programmed or controlled by a human. (Source: The paper)

The results showed that the participants could easily tell when the robot was being operated by another person.

But when the robot was operated by artificial intelligence, the participants guessed wrong more than 50 percent of the time.

Figure | Average accuracy of the Turing test. (Source: The paper)

This means that their AI passed the non-verbal Turing test.

However, the researchers also suggest that variability in human-like behavior may only be a necessary and insufficient condition for passing the non-verbal Turing test of physical AI, as it can also manifest in human environments.

Does artificial intelligence need to be like humans?

Artificial intelligence research has long targeted and measured human similarity, and Wykowska’s team’s research demonstrates that behavioral variability may be used to make robots more human-like.

Ziemke et al. argue that making AI less human-like might be a wiser approach, citing the case of self-driving cars and chatbots.

For example, when you are on the road preparing to cross a pedestrian crossing and see a car approaching you, from a distance, you may not be able to tell if it is an autonomous car, so you can only judge based on the behavior of the car .

(Source: Pixabay)

But even if you see someone sitting in front of the steering wheel, you can’t be sure if that person is actively controlling the vehicle or just monitoring the vehicle’s driving maneuvers.

“This has very important implications for traffic safety, and if a self-driving car fails to indicate to others whether it is in self-driving mode, it could lead to unsafe human-machine interactions.”

Some might say that ideally, you don’t need to know if a car is self-driving, because in the long run, self-driving cars may be better at driving than humans. But, for now, people’s trust in self-driving cars is far from enough.

Chatbots are closer to the real-world scenarios Turing initially tested. Many companies use chatbots in their online customer service, where conversation topics and interactions are relatively limited. In this context, chatbots are usually more or less indistinguishable from humans.

(Source: Pixabay)

So, the question arises, should businesses tell their customers about the non-human identities of chatbots? Once told, it often leads to negative consumer reactions, such as a drop in trust.

As the above cases illustrate, while human-like behavior may be an impressive achievement from an engineering perspective, the indistinguishability of humans and machines raises obvious psychological, ethical, and legal issues .

On the one hand, people interacting with these systems must know the nature of what they are interacting with to avoid deception. Taking chatbots as an example, California has enacted the Chatbot Information Disclosure Law since 2018, and explicit disclosure is a strict requirement.

On the other hand, there are more indistinguishable examples than chatbots and human customer service. For example, when it comes to autonomous driving, the interactions between autonomous vehicles and other road users do not have the same clear start and end point, they are often not one-to-one, and they have certain real-time constraints.

The question, then, is when and how the identity and capabilities of self-driving cars should be communicated.

Furthermore, fully autonomous vehicles may be decades away. As a result, mixed traffic and varying degrees of partial automation may become a reality for the foreseeable future.

There has been a lot of research on what kind of external interfaces self-driving cars might need to communicate with humans. Yet little is known about the complexities that vulnerable road users such as children and disabled people are actually able and willing to deal with.

Therefore, the general rule above, that “a person interacting with such a system must be informed about the nature of the interacting objects”, may only be possible to follow in more explicit cases.

Again, this ambivalence is reflected in discussions of social robotics research: given that humans tend to anthropomorphize mental states and assign them human-like properties, many researchers aim to make robots look and behave more like humans, such that They can then interact in a more or less human-like way.

However, it has also been argued that robots should be easily identifiable as machines to avoid overly anthropomorphic attributes and unrealistic expectations.

“So, it might be wiser to use these findings to make robots less human-like.” In the early days of AI, imitating humans might have been a common goal in the industry, “but in AI it has become part of everyday life. Today, we at least need to think about where it really makes sense to strive for human-like AI.”

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings